There is an image of Barbara Hepworth in a black furry coat and red headscarf that is displayed in her studio in St Ives. She is walking on the beach, among the rocks and seaweed and she appears as if she could fit inside one of her sculptures. I think of her walking along those beaches, smoothing stones collected from those sands in her pockets. I look at the stones and sticks and shells from there gathered here on my own desk. Talismans to touch. The last time I visited her studio, two summers ago now, I learnt her intention was for her works to be touched.

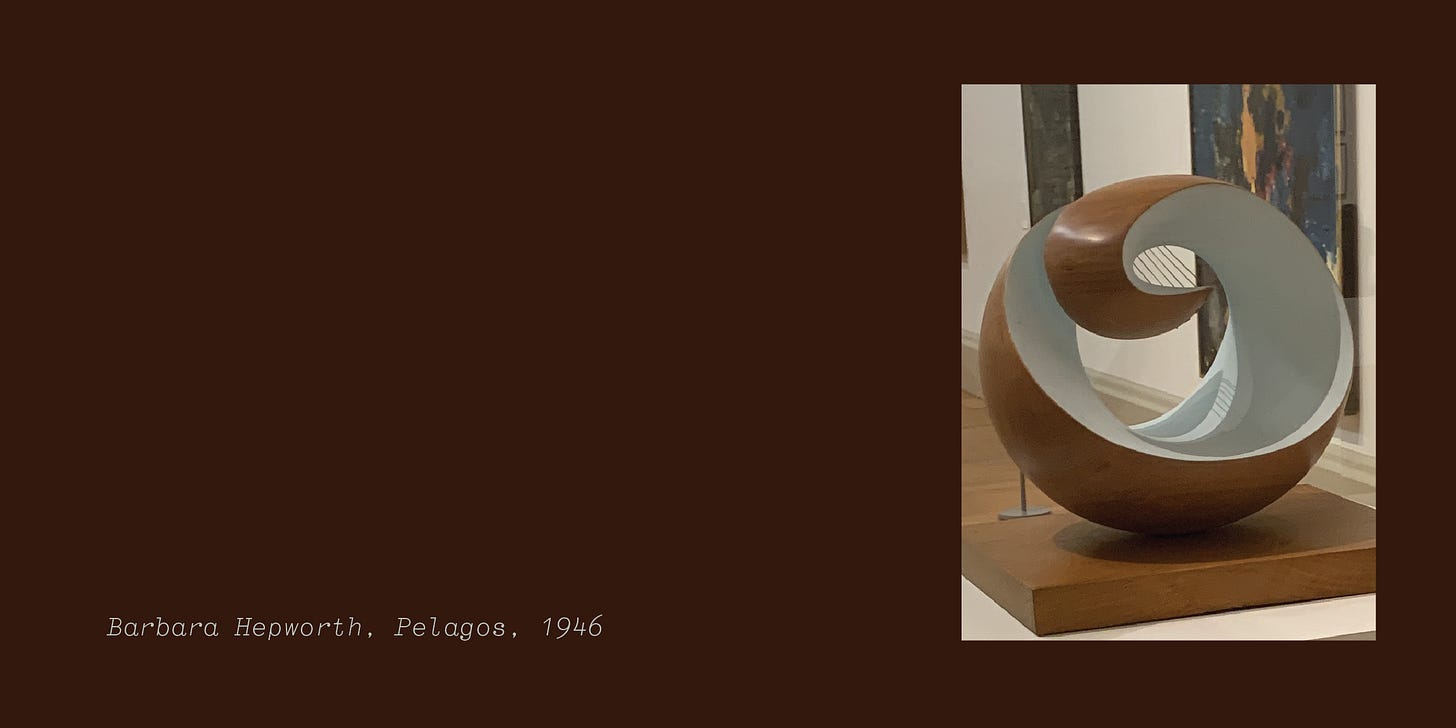

Pelagos is a fairly small sculpture on Hepworth’s scale. The name means sea in Greek. At the Tate it is encased in glass so I can’t reach into it. Instead I trace its lines, following the dance of light, inside out and outside in. Teetering on the edge of a memory, I wonder whether to plunge into its feeling.

Pelagos holds the balance of a wave in elm and string. Its exposed centre, painted pale blue, reveals a space that is full of taught lines and soft shadow. We see the strings which hold the shape together. I imagine how the strings would sound if I plucked them with my fingers. Like a breeze or a balanced chord?

The caption tells us it describes “containment and security rather than the dangers of an endless expanse of waters”: it’s how Hepworth felt in the bay at St.Ives. I remember a time when I was terrified of waves. I remember a time of welcoming their stinging spray against my skin.

Reading about Pelagos, I come across this quote: “The experience of the spectator is purely empathetic - that is to say, our senses are projected into the form, fill it and partake of its organisation…it becomes a mandala, an object which in contemplation confers on the troubled spirit a timeless serenity.”1 Its shape is a good one to fill.

The figure in the landscape was the starting point for a majority of Hepworth’s work, including Pelagos. Before it, I find the desire I harbour to be on the St Ives shore rise closer to the surface. From my city desk, I try to remember what it feels like to be in that landscape. A freedom to empty that feels full.

As I roll it around my head, Pelagos begins to sound like pelegrin, French for pilgrim. Barbara Hepworth moved to St Ives in 1939 with her young family at a time of war and found herself there at the centre of Modern British Art. She invested her energy into the community of abstract artists who found space to create in St Ives. I don’t know if she viewed it that way, but it reads as a pilgrimage of sorts.

At the door to this room at the Tate Britain, we are told we are joining the conversation in the 1940’s. From the outside it looks like modern art and its title hangs in the balance of “Fear and Freedom”. It holds a selection of fragmented perspectives grappling with expressing how that time and place felt as a human body. It makes sense why she sought to convey something essential about her experience in nature, in her own words trying to see the landscape as primitively as possible, before all her present fears.

I’ve just closed the covers of Perfection2, Vincenzo Latronico’s nomination for the International Booker Prize this year. Perhaps it’s unfair to compare a modern sculpture and a contemporary novel, Berlin and St Ives are very different places. But jumping ahead to 2025, a critic cited in its first pages described the novel as “A perfect picture of a generation…” Perfection exposes a lot of central questions in the belly of this generation, my generation. The experience it offers the reader of being both on the inside and the outside of our almost-current time period is unsettling and mesmerising.

I imagine the couple from Perfection would like a Barbara Hepworth on show in their apartment. Although if you touched it in the world of the novel, perhaps it would splinter. Just as the house plants gather dust. Nature doesn't orient them in a landscape or anchor them, observation does. Appearance does. Illusion does. The aesthetic and the sensual are disconnected. I suppose that’s what splitting life online and off does, each tab taking us further away from its natural touch point.

I look up from my desk and wish to be in the sea; to feel my body crack its crisp surface like a spoon into the sugar on a crème brûlée and then lie on the warm grey rocks of that coast again.

St Ives, Chris Stephens