I walked up the stairs of the Tate Britain and found myself in front of Gwen John’s 1902 Self Portrait. I first heard her name at a talk last year between Celia Paul, Edmund de Waal and Katy Hessel. But with Celia Paul’s book Letters to Gwen still on my reading list, I was frustrated to not know more about who I was standing in front of.

In A Room of One’s Own, 1890 - 1915, the table is set for the Bloomsbury Group, the Suffragettes, a bather by Pierre Bonnard. This is the period when women were first allowed to take steps beyond the domestic. What did that look like?

“All the time I spoke I saw her shoe and when it moved impatiently I knew without looking up what she was going to say: the whole of her seemed to be in her shoe”1

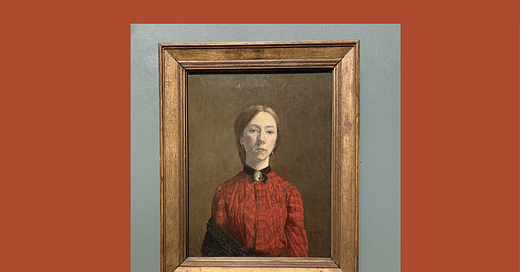

In this self portrait we don’t see John’s shoe. She paints herself cropped at the waist, her figure taking up about three quarters of the canvas, the rest filled with a haze of nutty brown. The only other detail included is her signature, floating by her left elbow. She is clothed in red tartan, the fabric folds with its patterned lines and a knitted shawl falls away from her arms. At her neck, black velvet is tied with a broach and from her ears fall delicate earrings.

It hangs in the same room as a tea set designed by the suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst and plenty of women painted in different rooms, sitting, bathing, thinking. It’s hard to decipher what the other framed characters might be thinking. With Gwen John, it’s easier to imagine. She’s thinking: I can do this.

The background takes on the tone of her determination: glowing, warm and strong. She knows what she stands for, she is at the centre of her own canvas. There are no distractions, no details to hint at the room she’s in or what is happening beyond.

Beside her hangs a portrait also painted by John in 1907, of Chloë Boughton-Leigh. Compositionally they are not so different. The two women are cropped, against soft brown backgrounds, although Boughton-Leigh’s hands fiddle as she sits in the artist’s studio. They both stare out of the canvas towards me. Where Boughton-Leigh appears absent, lost in her own internal world, John meets my eye and looks past me, towards her own purpose.

I’ve just read Celia Paul’s own Self-Portrait and I’m reminded of what she says about the practice of sitting for a painter, how people respond so differently to the patience and the stillness it requires. Whether being looked at for so long equates to being seen or whether it leaves one feeling lonelier than if they were alone.

I read more about Gwen John to try to see beyond the wooden frame into her wider life. Born in Wales in 1876, she studied art at the Slade from 1895 - 1898, the first art school in the UK to allow both male and female students. She attended with her brother, studied under Whistler and became a model and lover of Rodin in Paris. She spent most of her career in France, working around Matisse, Picasso, Brancusi and yet looking at her self portrait, I am distracted by none of these contemporaries.

I stop when I read words she wrote in a much-cited letter: “I may never have anything to express, except this desire for a more interior life.”2 By removing reference to a physical interior in her self portrait she side-steps the need to position herself anywhere other than in her own space.

Celia Paul described Gwen John as the painter who taught her that you didn’t need to shout to make a lot of noise. Like a suffragette’s tea set, John’s Self Portrait reveals the strength it took to step out of the house and into one’s own space in 1902.

This is the start of a practice of looking at art that speaks to me and taking the time to find out what it has to say. For now, they’re open to all but I’m introducing a paid option which will give you access to interviews with far more interesting people than I, and other creative writing. As ever, I’m very grateful for anyone who takes the time to make it all the way down here - ty!

Monday or Tuesday, Virginia Woolf

Gwen John: an Interior Life, Cecily Langdale, David Fraser Jenkins